Why Nerds Are More Clippable

McLuhan’s Laws of Media, applied to New Media

Someone else at a16z recently asked me, “What would Marshall McLuhan think about TBPN?” We are fortunate that, on occasion, we find just the right person to help us think through questions like this. Tomorrow in the a16z newsletter, we’re going to have a special guest, Andrew McLuhan (Marshall’s grandson), teach us about McLuhan’s Laws of Media, where they came from and how to employ them. Today in preparation, we have a fun prompt to introduce the Laws of Media that I hope you’ll enjoy. -AD

There’s a simple tech cliché that constantly proves itself true: “We overestimate the amount of change in the next 2 years, and underestimate it over 10 years.” It takes humility and imagination to recognize how much farther we have to go. This is especially necessary when we think about media, and how quickly power can shift to new groups of people who resonate particularly well with a new technology.

A new dominant media format has emerged in the last decade: the combination and integration of longform source material into shortform clips. The “Podcast into posts” pipeline is now a standard way that news and entertainment gets prospected and packaged, and we take it seriously at a16z as a leading indicator of not only where media is going, but more generally, “who is influential, and why.”

There is a deceptively simple trend here, which is only just beginning to play out, and is a pretty under-appreciated trend in world power dynamics: Nerds are more clippable; therefore, nerds have more power. This sounds silly but it is incredibly important.

Everyone in tech sort of appreciates this, in the sense that we’ve been one of the winners of this new format and it’s fun to win. But I think we’re still underestimating how important this trend is, and how it is reinforcing the “podcasts into posts” clip model as the premier path to influence. Just like pamphleting gave a platform to a certain kind of political theory nerd in the 18th and 19th century, which subsequently put those people in positions to shape the most important events in modern history, New Media is putting new kinds of people into very powerful situations.

Today we’ll use that question as an opportunity to use McLuhan’s Laws of Media to better grasp what has changed:

What are nerds and what is special about them

What is the New Media format (Longform source material; shortform clips)

What are McLuhan’s four Laws of Media

All together: why are nerds so clippable, and the coming institutionalization of New Media

Let’s go:

1. Nerds

First and foremost, we need a simple definition of what a “nerd” is for the purposes of this argument. Some obvious examples of who I’m talking about would be Elon, Alex Karp, Katherine Boyle and many of other people here at a16z, who are thoughtful, detail-oriented people that successfully reach large audiences now, but would really not have been able to a generation ago. The world of linear TV, of media training and polished storytelling, is really not nerds’ strong suit.

Paul Graham has a great essay about nerds that is mostly about adolescence but gets at something important for our purposes:

The main reason nerds are unpopular is that they have other things to think about. Their attention is drawn to books or the natural world, not fashions and parties. They’re like someone trying to play soccer while balancing a glass of water on his head. Other players who can focus their whole attention on the game beat them effortlessly, and wonder why they seem so incapable.

This is the essential bit: nerds are interested in a lot of things. They find the world too interesting. And so nerds often present as scattered, distracted, or even clumsy with their presentation or their approach to a topic because they have so many things going on in their mind. This makes nerds naturally bad presenters, according to the traditional rules of storytelling where you lay out a train track of your story and then you linearly proceed down the train track, without making any mistakes, in a fixed 3 to 5 minute media spot. Nerds are too interested in too many things to be good at traditional media. But now we have New Media, which seems to work much better for them. Why?

2. New Media: Podcasts, Clips and Tweets

We use the term “New Media” to mean a lot of different formats and practices, but the heart of the mechanic that’s important here is the following sequence:

Longform source material (for example: hour-long conversations in podcasts; longform writing, live events)

Clips and packages of highlight content that spread virally on social media.

This sequence of “longform source material, extracted short-form packaged product” is the essential atomic unit of media now. We’re still pretty early in how this change shapes everything downstream.

Live sports and other longform sources have gone through their own “clip revolution”, which is interesting in its own right. But in our world, the podcast conversation has become the essential headwater source of shareable New Media material, and it lends itself very well to the “nerd” archetype who finds the whole world interesting, and has really interesting arguments to share; they just don’t flow linearly. They require an open-ended prospecting expedition to go find them.

Podcasts existed for quite some time in a proto-format where they were heavily produced, like NPR radio shows (Radiolab, Serial, the Gimlet shows…); it took us a few years to figure out that actually the real format was Odd Lots. Find interesting people to talk to each other; get it segmented, clipped and shared out. Here’s Marc a few months ago, on how podcasting has completely changed the bar of “speaking like an authority figure” compared to television:

The cliche is, you’re watching an interview with somebody on cable news and it just starts to get interesting and then the host says, “Well, we’ll have to leave it there, thank you for coming in.”

Why do you have to leave it there? You’ve got the person in the studio. You could go for another hour. You could go for another three hours. But you choose not to.

In contrast, what does the three-hour Rogan or Lex Friedman episode have going for it? It doesn’t have that problem where as soon as it gets interesting, “we have to leave it there.” You can actually fully articulate a point of view on any topic. So the range of topics has expanded a lot. And it’s all on demand, and they segment the videos and so you can decide which parts of it you want to watch.

Is this going to change the skill set and aptitude it takes to be an authority figure? The new threshold is that you have to be able to go on a long form podcast and talk for three hours and be interesting. Traditional media training does not teach you how to do that, and a large number of people who have been in charge of things for the last 50 years are definitely not able to do that. And so, whether that is going to be the new threshold for success in the public arena, I think is an interesting question.

3. McLuhan’s Laws of Media

The last thing we need to cover is McLuhan’s Laws of Media themselves.

Compared to other works by McLuhan (including his essential book Understanding Media, which can be admittedly challenging to the uninitiated), his four Laws of Media are pretty approachable. He insisted that all forms of media have four essential characteristics, which McLuhan calls the “Tetrad”:

They enhance some innate human capability, letting us do it louder, faster, farther. This attribute of the technology typically comes to mind first: what do we do with it that feels right?

They make obsolete some incumbent set of capacities we already have. (The tech industry’s familiarity with “disruption theory” is helpful here: the obsoleted technology becomes less relevant because its winning dimensions of performance are no longer the important ones.)

They retrieve some older tradition or deep subconscious competency, and bring it back to the forefront. Some behaviour that we innately know how to do, in our biology and in our old habits, finds unexpectedly resonant product-market fit with the new media format. This can be hard to predict in advance.

They reverse into antithetical properties when pushed to their limits. The final achievement of the format is when it’s pushed so hard it starts behaving in the paradoxically opposite way it was intended.

For example, let’s take Google Docs as a familiar case:

Google Docs enhances our ability to collaborate on a document (as opposed to actually writing it); it is editing and commenting software.

It obsolesces the word processor. Writing something in one shot, and sending it for holistic reaction or editing (also in one discrete shot), and then sharing a finished memo, tends to get outcompeted by “There’s the first draft of the Google doc, please jump in with comments.”

It retrieves talmudic commentary; contemporary executive version. Inside of companies, the highest signal information is often comment chains between executives talking about the subject matter in a Google Doc, which is then linked to as “For source of truth, see this comment.”

It reverses into chat. Documents are never completed, if they have anything interesting to say. The comments cannot be resolved as they have become the content. And so the “finished” Google Doc is the one that is never actually published or printed, it reverses into an oral discussion that is exported as a source of truth.

These four properties, applied to the media in question, can help us understand our tools better and appreciate their counterintuitive consequences.

The New Media Nerd Tetrad

Now we’re ready to go. We’re going to apply McLuhan’s tetrad technique on the combined technology of “podcasts + clips + social sharing”, since it is truly a single media format that works together:

What does New Media enhance?

The first innovation of New Media is that it is an improved prospecting method for idea generation for clips that ultimately go viral. And the first step of idea generation is getting it out of the person, and removing their inhibition. The podcast-to-clip sequence has turned out to be lethally good at this, specifically for nerds.

There are a few reasons why. Remember that the essential thing about nerds is they have too many ideas; they think too many things are interesting. So, without an expansive, open-ended format, you are not going to discover the tight, clippable form of the argument that you need to go viral. Podcasts enhance a very specific form of idea exposition: “take all the time you need to find the path to the clippable form; you probably don’t even know it yet at the outset, we are going to find it together.”

This observation is not especially new; interviewing has existed for a long time and a good interviewer will try to do this with any guest. The podcast format simply widens the net, and lowers the cost of exploration. What’s more novel, though, is what New Media obsolesces:

What does New Media make obsolete?

A non-obvious way in which podcasts and social media timelines are mutually compatible is that neither of them have a necessarily defined sequence. You can consume them in a completely scrambled order and they still make sense. This is an essential part of why they are so effective at idea prospecting, and also an important factor in why “nerd content” works so much better here than it does in other places.

The timeline presenting in a scrambled order is an essential part of what makes it fun. You wake up in the morning and see what “today’s joke” is, but you see the punchlines and the riffs first, and you actually have to dig backwards to find out what the reference actually is, and then the joke clicks into place. (Note that this is true for serious content too, not just jokes!) You’re rewarded for doing work (of finding the reference), which feels good, and is why we go back.

It’s less obvious when you think about the source material of a podcast as also not being subject to a linear constraint. But it’s equally the case. Many great podcast sequences start from specific observations or questions (“reactions” to the hidden grand idea that has yet to reveal itself) and then back their way into the grand idea. Note something important here, which is that “conventionally” good talkers do not tell stories this way. Their narrative is purposeful, it has a direction to it, it arrives at its intended conclusion. Nerds, on the other hand, usually don’t think like this. Their ideas are great, but they’re scattered and emerge out-of-sequence.

These two factors, together, I think explain a large part of why nerds are going viral more. The thing nerds are bad at - the linear storytelling format, which rewards linear storytellers - has become obsolete. The nonlinear podcast format successfully prospects and extracts the interesting argument; the nonlinear timeline format successfully primes the audience to first hear the punchline, then backfill the context - an essential skillset for reading nerd content, which requires that kind of approach. Clips make the nerd ideas more accessible; the timeline makes the reader more amenable.

What does New Media retrieve?

The old behavior that reemerges in the New Media format conveniently has a name - “Pamphleting.” This is the centuries-old vessel for nerds to go viral on the timeline.

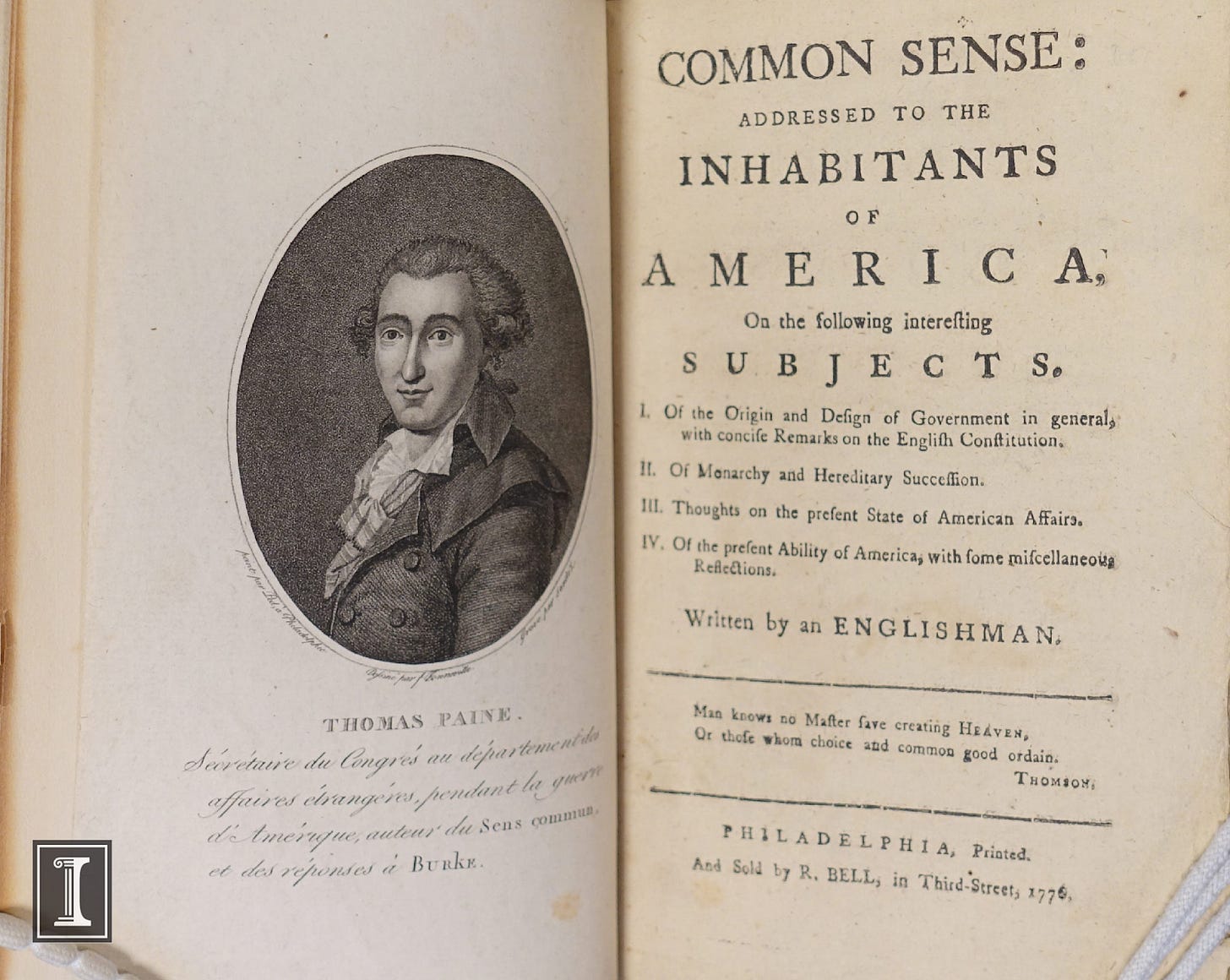

Pamphlets are often referred to as “the original social media”, where writers would argue stances on serious topics like religious or revolutionary movements, often pseudonymously, like anon accounts today. Many great ideological turning points in world history (the American, French and Russian revolutions, for example) are associated with famous pamphlets that went historically viral (Thomas Payne’s Common Sense, the anonymous Histoire de la Conversion d’une Dame Parisienne, Marx’s Communist Manifesto).

These pamphlets were the original “posts” back then, and many of them came from lengthy dialogue sessions at local salons and parlor sessions which would’ve been the equivalent of “hosted podcasts”. Salons plus pamphlets created the same mechanism as “podcasts plus clips”, a prospecting mechanism combined with a clip & broadcast mechanism that gave nerds a resonant platform. There is no doubt in my mind that these pamphlets were not so much the contemporary “posts”, they were the contemporary clips, synthesized from a familiar kind of idea prospecting.

Pamphleting was an important development in world history, because it put nerds into positions of influence and power. The nerds usually weren’t necessarily the people drawing the biggest laughs and showing the quickest wit in the salons themselves; but they could clip the right extracts and gain influence on the outside. Notable pieces of writing like The Federalist papers, On Liberty, The New Statesman, and Antonio Gramsci’s prison notebooks not only contributed the important ideas themselves, they also as a medium pushed enough of the contemporary nerds into common spaces and into positions of decision-making authority that they pushed quite a few major events in world history over the tipping point of realization.

The real behavior that is being retrieved, correspondingly, is “nerd-as-political-theorist”, even for people whose content is not at all political. Over time, the nerd politics become what politics are (see, Gamergate). As the clip format accelerates, you have to ask to what degree this accelerates, or what stops it.

What does New Media Reverse into?

Podcasts have been around for a while; so has social media. It took a few years for everyone to figure out that clips were the truly native format that bridged between longform content prospecting and shortform content propagation. Now the format is truly off to the races, and we have to anticipate where things go.

The semi-obvious and very funny logical conclusion of the New Media story arc is for it to fully collapse back into corporate media again. In our world, TBPN is the vanguard experiment for what happens when you vacuum up all of the nerds, nerd jokes, and reasonably serious nerd content that was organically getting clipped onto the timeline already, and bundle it into an ESPN-style “corporate clip show” that brings those people back into a more conventional 3 to 5 minute TV-style spot.

John really cooked with this one

The funny reversal here with TBPN specifically is now you have ESPN, but by nerds and for nerds, so we all love it. But the reversal equally applies to venture firms like us, who do this job of finding the talented nerds and their messages, and helping to host, rebrand, repackage, and redistribute it. The major inversion, in the new institutional setup versus the old, was it used to be that “non-nerd” institutions would lend audiences credibility to overcome their nerdiness; whereas now it’s actually the guests’ clippable nerdiness that gives the institutions their legitimacy. (The Odd Lots podcast is a perfect example of a nerdy show with perfect guests that has quickly risen to prominence in our new media environment).

The two-stage prospect-and-propagate model we had with podcasts and clips is now a three-stage model for viral content: prospecting for ideas from podcasts, propagating the winning ones via viral clips, and then legitimizing them via branded channels. This completes what I think of as the accelerating flywheel of nerd virality where enough infrastructure has assembled around “high quality but nonlinear nerd narratives” in a way that we now have a mature prospecting pipeline, refining stack, and distribution mechanism for end consumption.

It’s relatively less independent in the way it once was - but the reinforcing effect will persist in its newly institutional state; “nerds are more clippable, therefore nerds get more power”.

To conclude: it is worth asking the question, “could we only just be at the very beginning of this trend? How far could it go, if the Laws of Media around this format actually hold for some time? Our job here is to give the world’s founders power; that’s why we do what we do.

This newsletter is provided for informational purposes only, and should not be relied upon as legal, business, investment, or tax advice. Furthermore, this content is not investment advice, nor is it intended for use by any investors or prospective investors in any a16z funds. This newsletter may link to other websites or contain other information obtained from third-party sources - a16z has not independently verified nor makes any representations about the current or enduring accuracy of such information. If this content includes third-party advertisements, a16z has not reviewed such advertisements and does not endorse any advertising content or related companies contained therein. Any investments or portfolio companies mentioned, referred to, or described are not representative of all investments in vehicles managed by a16z; visit https://a16z.com/investment-list/ for a full list of investments. Other important information can be found at a16z.com/disclosures. You’re receiving this newsletter since you opted in earlier; if you would like to opt out of future newsletters you may unsubscribe immediately.