Operating on DNA is more like surgery than medicine

The regulatory path and potential of genetic surgery

| America | Tech | Opinion | Culture | Charts |

Last February, a baby lay in an ICU crib in Philadelphia. His blood flooded with ammonia that his liver could not clear. The diagnosis: severe CPS1 deficiency, caused by a rare single‑gene mutation. Not too long ago the prognosis would have been grim: brain damage and an early death. But not this time.

A team of doctors and scientists at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and the University of Pennsylvania sequenced his DNA, designed a custom gene‑editor to fix the typo in his CPS1 gene, manufactured it on demand, and infused it into his bloodstream. Baby KJ Muldoon became the first person treated with a gene‑editing therapy built specifically for his mutation. All told, the process took about six months and cost less than $1 million. Today, Baby KJ is thriving and seemingly cured. A recent video shows him taking his first steps, two Christmas trees twinkling in the background.

If you and I get a prescription to a specific drug, our dosage may differ but we both get the exact same molecule. What happened to Baby KJ was fundamentally different: an interventional team used specialised tools to repair a unique defect in one person – in this case the defect was a specific deleterious mutation in his CPS1 gene. More than gene therapy, this is genetic surgery. And a growing array of molecular instruments fill an expanding surgical cabinet: CRISPR‑Cas9, the Nobel-prize winning genome‑editing system to cut DNA, base editors swap one DNA letter for another without cutting, prime editors act like DNA search‑and‑replace, engineered viruses and small bubbles of fat deliver these editors to the specific cells and organs where intervention is needed. More will undoubtedly follow.

Genetic surgery needs a new regulatory paradigm

By definition, a rare genetic disease is a condition that affects less than 200,000 people in the United States. By that measure, there are on the order of 10,000 rare genetic conditions, affecting roughly 30 million people in the US; on the wispy end of that long tail, some of these conditions are so rare that there may only be a handful (“n-of-some”) or even just a single known case (“n-of-1”). These conditions are individually rare but collectively common. Many are devastatingly ill patients with desperately few options; 95% have no FDA‑approved treatment. Genetic surgery could in principle correct the errors underlying the majority of these conditions if a) the disease‑causing genetic variant is known and b) a gene editor can be safely delivered to the right place to correct the error (ie to the liver, the eye, the brain).

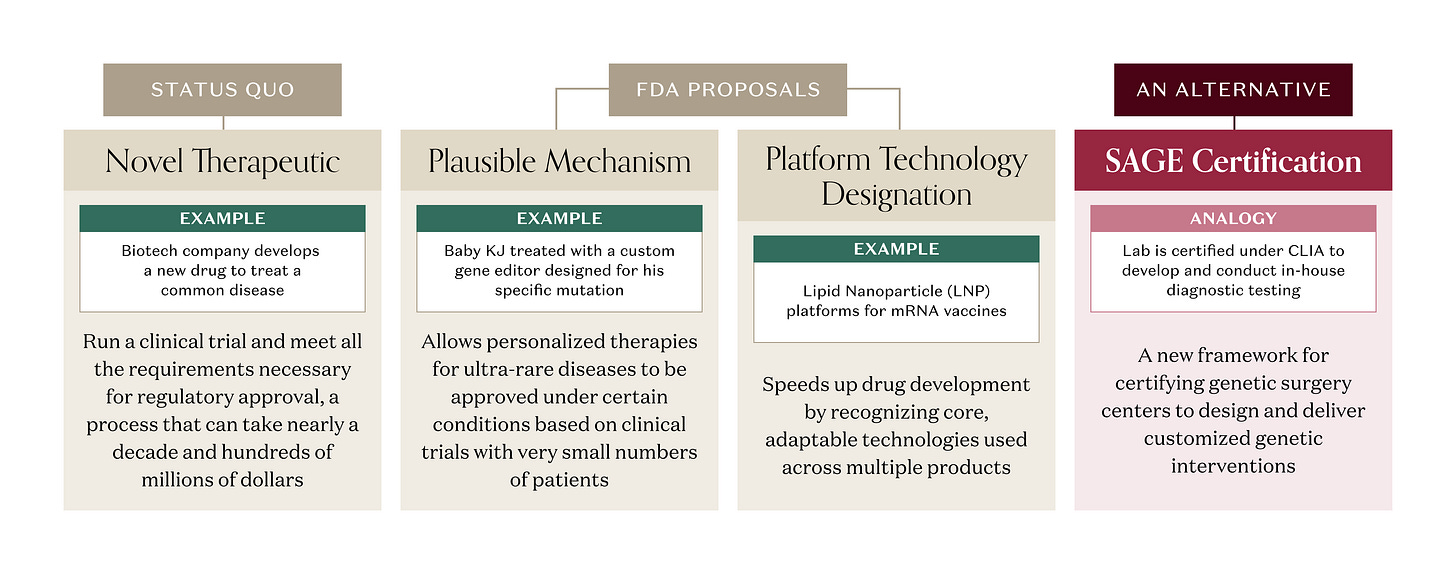

But there’s a catch. Under current FDA rules, a gene editor designed to correct a specific mutation is regulated as a novel therapeutic, even if the same components (gene editor, delivery vehicle) have been validated in treating a different mutation for a different disease. A company developing that genetic medicine would still need to run a clinical trial and meet all the requirements necessary for approval, a process that can take nearly a decade and hundreds of millions of dollars. That approach can work for a single genetic disease with a larger patient population, where the R&D investment can generate a good ROI. But a single genetic disease often isn’t “single” at all. One gene can harbor hundreds of different pathogenic variants. A disease with 100 distinct mutations that all break the same gene could require 100 separate approved therapies. And for the rarest diseases, there are no therapeutic R&D efforts at all; the patient populations are tiny, timelines long, and fixed costs enormous. Too often, the math doesn’t pencil.

The FDA is on the case. In late 2025, agency leadership proposed a new “plausible mechanism” pathway that would allow personalised therapies for ultra‑rare diseases to be approved based on clinical trials with very small numbers of patients when the disease mechanism is clear, the genetic mutation is known, and the clinical benefit matches what you’d expect from fixing that error – a critical step towards an enduring regulatory framework that clarifies essential scientific and product-development considerations for these therapies. The Baby KJ case is explicitly cited as the prototype for this approach. The FDA had previously proposed a “platform technology designation” to, in part, address the reusable component element of repurposing a delivery vehicle and customizing a proven genetic editor. These initiatives and many others under consideration by FDA will accelerate the path for therapies to reach patients.

What if there were a better approach?

What if Baby KJ heralded a new era of interventional genetics where we chose to treat genetic surgery not as a therapeutic product but rather as an interventional procedure? Medicine already does high‑risk interventions — think open heart surgery. The FDA regulates the devices (stents, valves, catheters) and drugs involved, but it does not regulate each bypass as a “product” because no two surgeries are alike. Surgery is overseen by state medical boards, hospital credentialing committees, professional societies, and outcomes registries; it’s a systems approach rather than product-by-product approval. We already know how to regulate risky, stochastic procedures that live inside well‑run institutions.

A mass produced diagnostic kit, an in vitro diagnostic (IVD), is regulated by the FDA as a product that requires rigorous testing for approval – our pregnancy tests and blood glucose monitors need to be unfailingly accurate. But CMS and FDA use another playbook for homebrew tests designed and validated in‑house by hospitals and reference labs. Those tests you get when they draw too many vials of blood at your doctor’s office or at Quest, known as Laboratory-Developed Tests (LDTs), are regulated under Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA), which certify the lab’s processes, personnel, and quality systems, rather than having the FDA review each individual test a lab provides. FDA has long recognized LDTs as diagnostics in principle, but has chosen to exercise “enforcement discretion” and certify the labs as being CLIA-compliant instead of treating every LDT like a boxed product.

If FDA and HHS were to use enforcement discretion, genetic surgery could live in that same regulatory friendzone. Imagine a CLIA-like approach where FDA creates a new framework for certifying qualified centers capable of designing customized genetic interventions à la Baby KJ: say, a Standards for Advanced Genetic Editing (SAGE) program – “the CLIA for interventional genetics.” Instead of approving every individual edit as a therapy, regulators could use SAGE certification to approve validated platforms (specific prime‑editing systems, delivery vehicles) and the process for designing customized, one-off genetic interventions. Like CLIA, SAGE would make accredited centers, not individual edits, the primary unit of regulation.

The FDA’s highest mandate is to ensure the safety and efficacy of human therapeutics. First, do no harm. But in instances of genetic disease with no approved therapy, doing nothing is perhaps the greatest harm. And doing something is not without risk. Not every surgery is successful; attempts at genetic intervention will fail and some may result in death. So it is imperative to proceed with caution and care. To be SAGE-certified, a center for genetic surgery would need to demonstrate it has the requisite expertise to establish multidisciplinary boards to review and select cases, to customize validated editing platforms, to design standardized processes with defined quality gates, to establish clinical-grade batch manufacturing capabilities and to track safety and outcomes for every patient treated.

Biotech companies are built around pipelines of products: each with a target product profile, market size, and probability of success. But centers for genetic surgery would instead have pipelines of patients: a queue of Baby KJs, each with their own devastating mutation, triaged by urgency and tractability, awaiting customized interventions. Under SAGE, a genetic surgery center wouldn’t need to invest years and millions to run clinical trials and establish commercial-scale manufacturing capabilities for FDA approval; it would be able to start treating patients as they were identified and evaluated. It wouldn’t be in the business of blockbusters, but would be a barrier-breaker for patients that are otherwise at a dead end.

The first genetic surgery centers would be based within leading institutions in our biomedical ecosystems like Boston (Harvard, MIT), Philadelphia (UPenn, CHoP), and San Francisco (Stanford, UCSF). As genetic surgery is validated as a practice, bespokeness will give way to industrialization and we may see the emergence of de novo SAGE-certified start-ups. As China biotech rises, genetic surgery can’t be easily offshored; by necessity it will be Made in the USA for our most vulnerable Americans. And there will be an important ancillary benefit: genetic data exhaust. As patients undergo genetic surgery, we will learn a great deal about how to design, dose and deliver genetic editors more generally; knowledge that will feed back to therapeutic programs targeting larger patient populations. Like technology, it may be limited first for the few but then benefits the masses.

There is of course the question of who pays, how and how much? We routinely cover expensive one-time interventions like open-heart surgery. If Baby KJ is any guide, genetic surgery will cost on the order of a million dollars, at least initially; a big downpayment with benefits that last an extended lifetime. Governments and industry will have to work out ways to pay for potential cures. We’re already seeing new models like outcomes‑based contracts, gene therapy reinsurance pools, even mortgages for medicines. In biotech, reimbursement is the daughter of invention.

We are at the beginning and there is still much to figure out; in genetic medicine, small changes carry enormous consequences. But for a brighter future with genetic surgery, and better days for those patients that would benefit, we won’t need a surgeon – just a SAGE.

This newsletter is provided for informational purposes only, and should not be relied upon as legal, business, investment, or tax advice. Furthermore, this content is not investment advice, nor is it intended for use by any investors or prospective investors in any a16z funds. This newsletter may link to other websites or contain other information obtained from third-party sources - a16z has not independently verified nor makes any representations about the current or enduring accuracy of such information. If this content includes third-party advertisements, a16z has not reviewed such advertisements and does not endorse any advertising content or related companies contained therein. Any investments or portfolio companies mentioned, referred to, or described are not representative of all investments in vehicles managed by a16z; visit https://a16z.com/investment-list/ for a full list of investments. Other important information can be found at a16z.com/disclosures. You’re receiving this newsletter since you opted in earlier; if you would like to opt out of future newsletters you may unsubscribe immediately.

It’s tricky because CRISPR based editing is not as simple as it’s portrayed here. Each time you design a guide RNA there is potential for off target effects. So essentially custom targets for each individual are a “different medicine”. We don’t know for sure how each will behave in individual patients. Patients will need to know the risk…there is a strong chance it could correct the genetic defect and a some level of probability there could be off target side effect. One other complication is not all targets are the same in the genome…some genes share great similarities in coding or exonic sequence. The specificity of loci to be corrected would likely require screening of the reagents required to meet a certain efficacy before it could be applied to the human body. Delivery is also no walk in the park…how do you correct a gene with a germline mutation that is primiarily expressed in liver as opposed to circulating lymphocytes etc. While the SAGE idea is interesting we are so far away from this technology being ready to go for any possible case. There is also the other complication of diseases modified by epigenetic effects or even gene-gene interactions. So in other words there may only be a limited number of rare diseases editing will be available. Just like precision medicine, we can identify somatic mutations in tumors that give indication to the drug the patient is most likely to respond to, or likely to kill most of the tumor. However, just like germline editing, precision oncology is mostly limited by the drugs available and there is still limited knowledge why say genetic features predict some effects for some but not for others. I like the idea of SAGE but putting this into practice is going to be challenging and editing will not be as so widely available as this article portrays it.

Radically invasive, at that. Wildly experimental at best.