Jevons or Bust

The cheaper they get, the more we use? A quick look at some AI token data

Last week we wrote a piece called “Why AC is cheap, but AC repair is a luxury”, on the interplay between the Baumol Effect and Jevons Paradox. Whenever you have massive productivity increases in one sector of the economy, you see weird things happen economically, both inside and outside of that industry. Both phenomena come from the same root cause: the dramatic increase in demand, in both quantity and variety, unlocked by technology and productivity.

We’re following up this week by taking an inside peek at some of those numbers, many of whom are thanks to our friends at YipitData.

Jevons, followed up

The following kind of graphic is an important sign that something big is happening.

They’re imperfect, and they can only represent the present and past, but not the future, but insofar as they reflect demand for AI, then they bear most directly on this question: are GPUs following a boom and bust pattern, or a Jevons-like new frontier? Are we getting faster horses, or is this the advent of the automobile?

What we want, is a continued demonstration of what we’ve seen thus far:

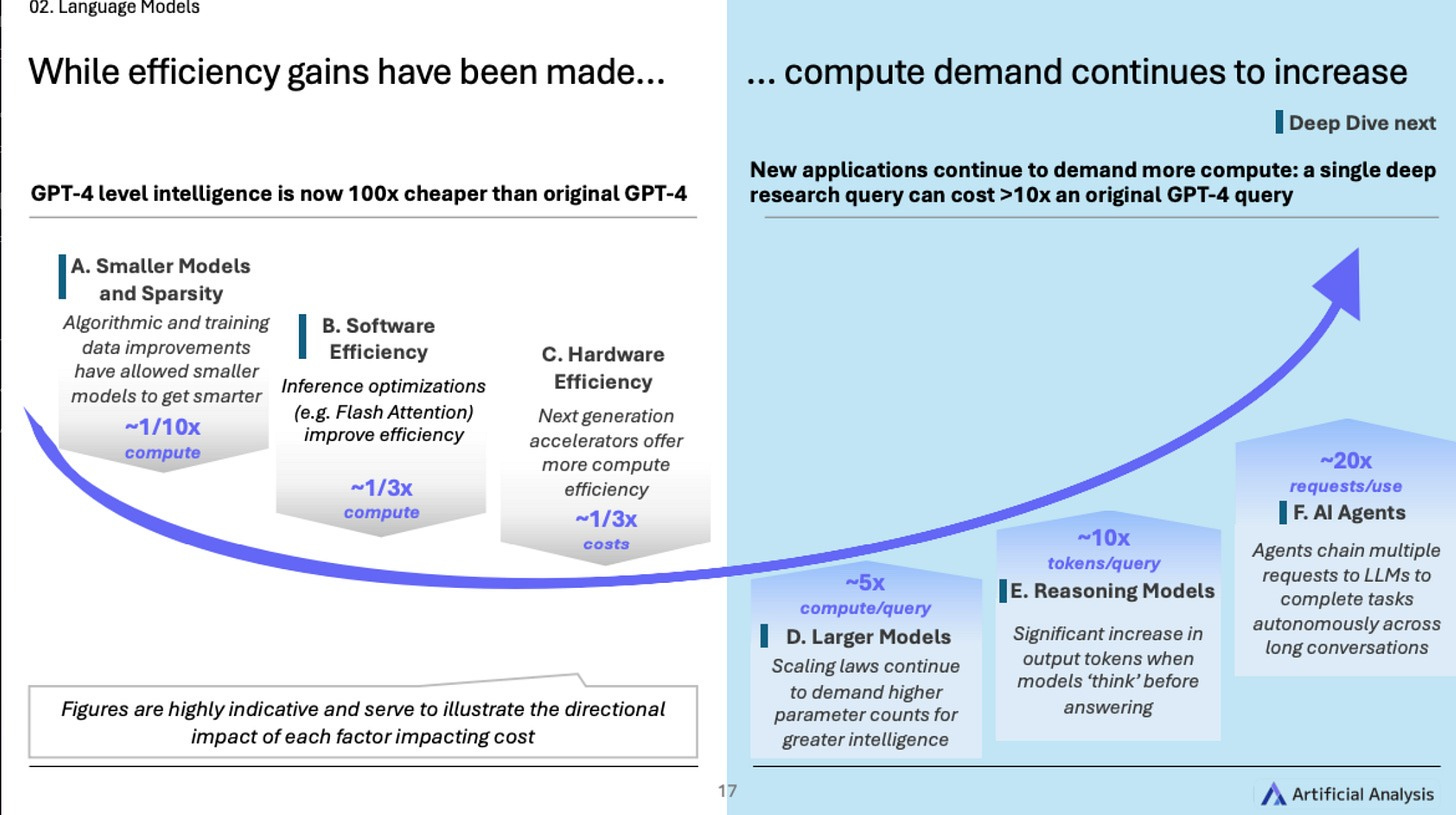

Models and compute get progressively more efficient, driving demand up-and-to-right. These figures are “illustrative,” but you get the idea: this is Jevons in full-effect. Increased efficiency drives increased demand.

Everyone pays a lot of attention to the sheer magnitude of the AI capex buildout (for good reason), but in some ways it’s the wrong place to look, or rather it’s a very incomplete picture.

As long as real demand continues to grow—not speculative “dark fiber” demand or expectations for future demand—but real, present-day actual consumption patterns, and those consumption patterns are enduring, then the size of the buildout is sort of besides the point.

All of which is a somewhat long-winded introduction to draw your attention to the following charts on AI demand. It’s definitely real, and it’s spectacular.

One (point three) quadrillion tokens

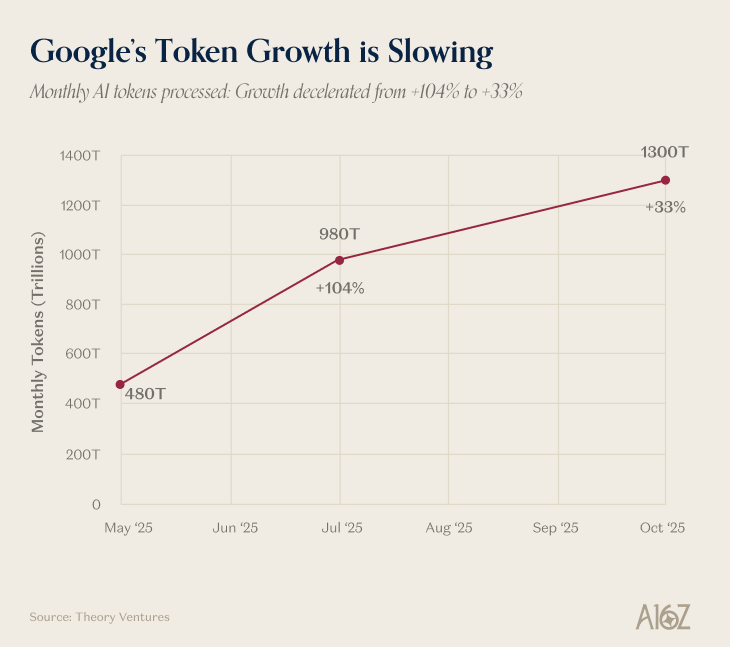

Back in May, Google announced that monthly token consumption had grown to 480 trillion:

That’s a 50X increase from where token consumption was only a year prior.

In November, Google came back and announced that “token consumption is so high, we’re going to use a make-believe number to express it,” or something like that:

That’s 1.3 Quadrillion monthly tokens across all Google surfaces.

Quadrillion is a whole lot of tokens. Technically, quadrillion is not a make-believe number, but it might as well be. I’m pretty sure it’s the first time quadrillion has ever been used in an earnings call, so there’s that.

Is the rate and pace of token-consumption growth slowing down a bit? Yeah, maybe:

While consumption doubled from Q1 to Q2, it only increased by 33% by Q3.

Why is consumption growth slowing down? It’s hard to know, but for present purposes, suffice it to say that the rise has been meteoric, and it is still, in fact, growing. “Meteoric, but slightly less-so, recently” is a fairly consistent pattern.

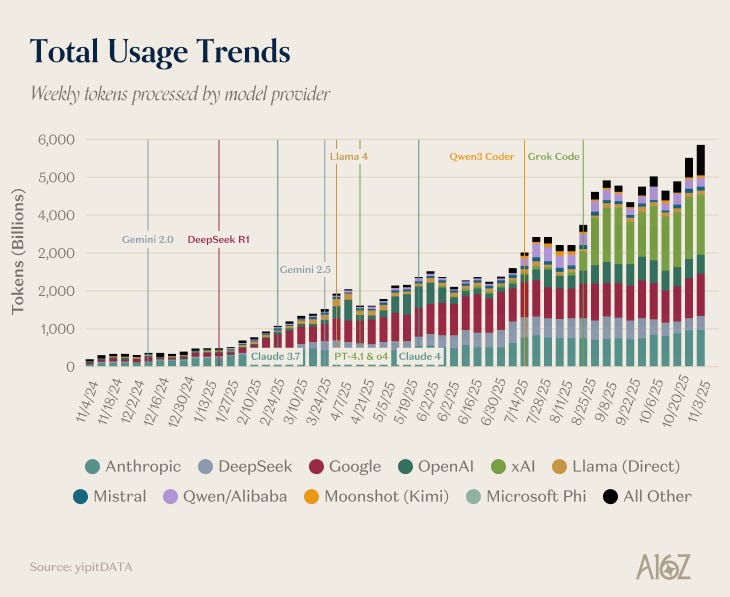

OpenRouter, which measures token consumption for apps that opt-in to its ecosystem (and therefore likely undercounts direct consumption, especially for models like ChatGPT) shows a similar pattern:

Weekly token consumption has gone from ~300B to just under 6 trillion in just about a year.

That’s basically a 19x yoy increase, and again, OpenAI’s models don’t crack the Top10 among the models captured by OpenRouter, so this is only a partial picture of AI demand growth.

Did growth curiously flat-line in September? Sure, it certainly does appear that way. But it flatlined in August too, and in June, and in April, with each flat period followed by a substantial step-up to new highs.

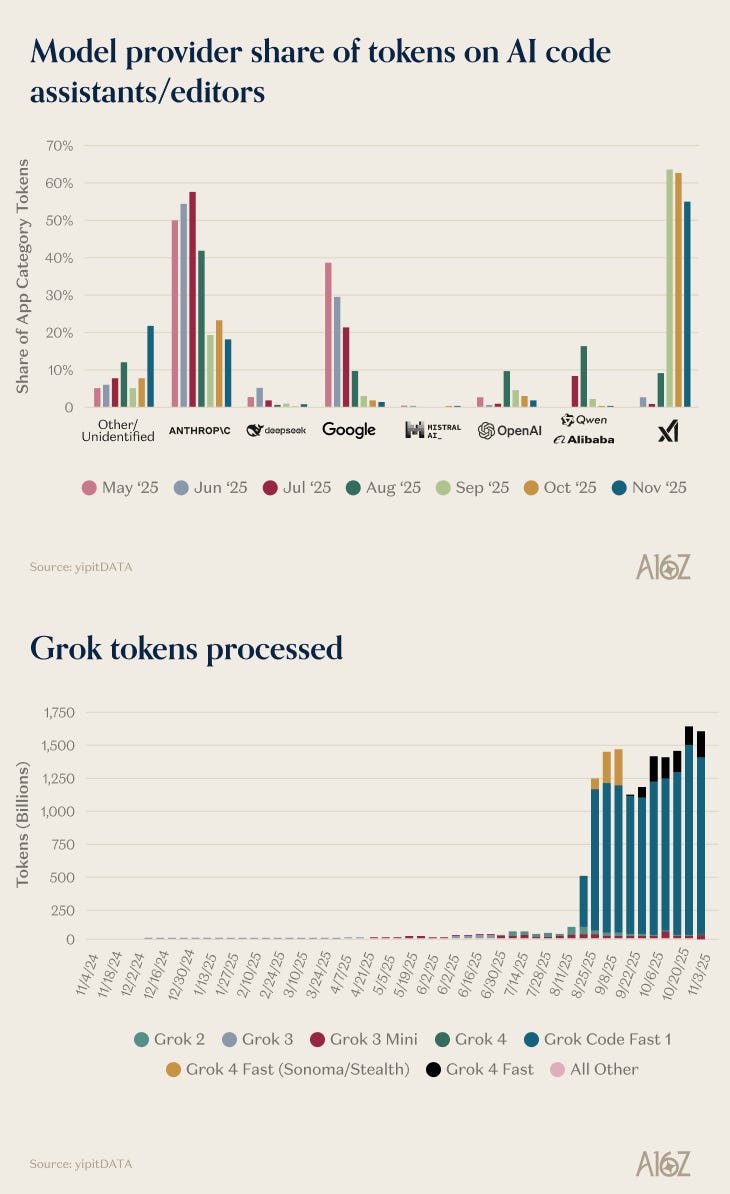

The most recent new high was driven almost entirely by xAI’s latest release, that came outta nowhere to capture ~60% of the code-gen tokens processed through OpenRouter:

xAI went from a rounding error to an official code-gen player in the blink of an eye.

Again, past-performance does not predict future results, but there’s a lot of evidence that demand for AI continues to grow. And that every apparent plateau is quickly exceeded by a new entrant into the marketplace of models.

Prices down, demand up

OK, so demand for AI grows, but is it paying demand? And more importantly, for the Jevons question, is price the throttle, such that greater efficiency is the unlock for even more demand?

That too, is hard to say, but based on OpenRouter’s data (and Yipit’s math), the answer is “seems like it, but it’s a little hard to tell.”

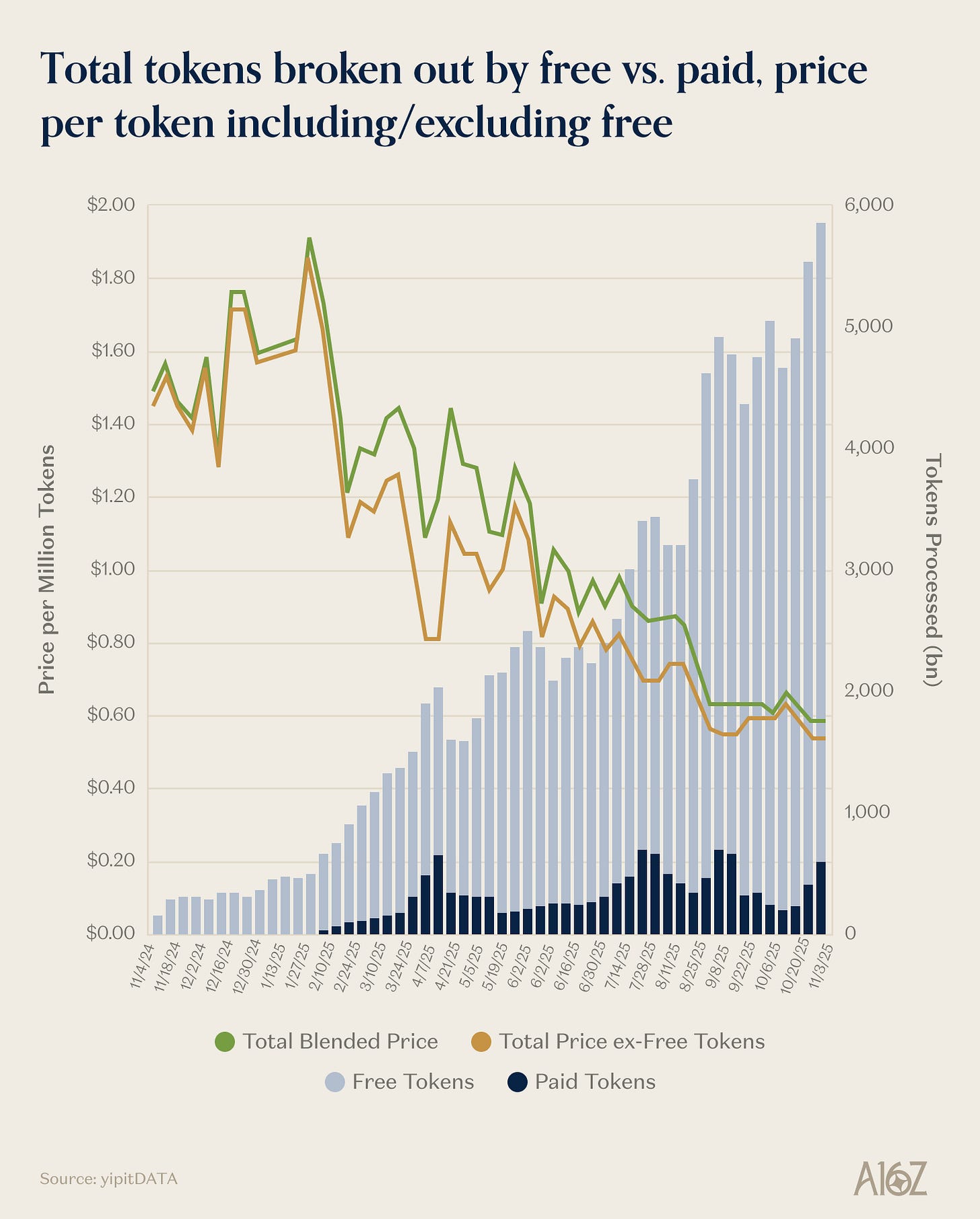

Here’s a cut of token-prices against tokens-processed that shows tokens getting cheaper, and paid consumption rising:

$/million tokens is about a third of what it was in February, while tokens consumed has quintupled over that same period.

Free tokens are playing a surprisingly small role here. Plus, if you’ll notice, every step up in token consumption appears to be accompanied by a drop down in pricing. To repeat, this is an incomplete picture, and eye-balling a chart isn’t correlation, but ‘price go down, demand goes up’ is a better than defensible interpretation of the chart.

In general, there are signs of growing demand in the most likely places to look for them.

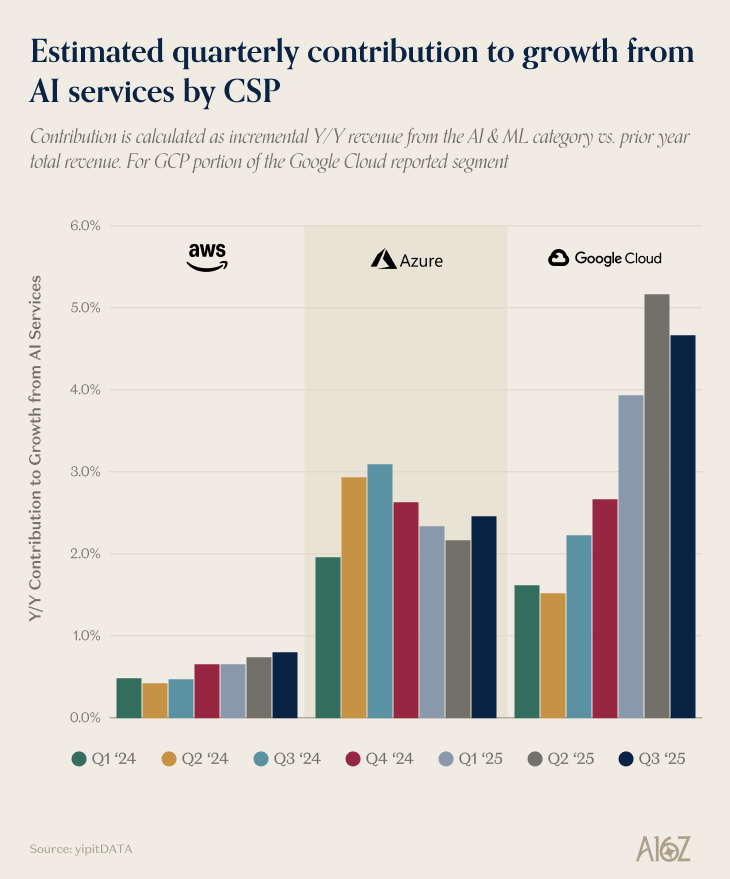

Is AI driving incremental revenue to the big cloud providers (who are spending all this capex)?

Yes, it appears that it is:

Estimated incremental cloud revenue from AI/ML usage is growing every quarter, from ~1% to 5%, depending on the company.

AWS is growing a little more quickly every quarter, Azure has reaccelerated recently, and Google has accelerated the most. These are relatively small numbers, but (for context) we’re also talking about fully-scaled (but still growing) multibillion dollar run-rate businesses

The focus on AI shows up in the code too.

6 out of the 10 fastest growing open-source projects on github are AI-focused:

Code assistants, and other ‘work with AI’ adjacent projects predominate the hottest new things in the open-source landscape.

What precisely developers are making with that AI-assisted code is a separate question, but it’s hard to imagine a future scenario where AI isn’t a bedrock component of the engineering toolkit. Heck, we’re rapidly approaching the moment where AI is a bedrock component of the AI toolkit, insofar as agents begin to call their own AI tools to help with their tasks.

Beyond faster horses

So does that settle it? Is AI definitely a Jevonic-non-bubble, instead of a capex binge that ends badly?

No, of course not. We don’t know yet. The counterfactual case to this buildout remains easy to understand:

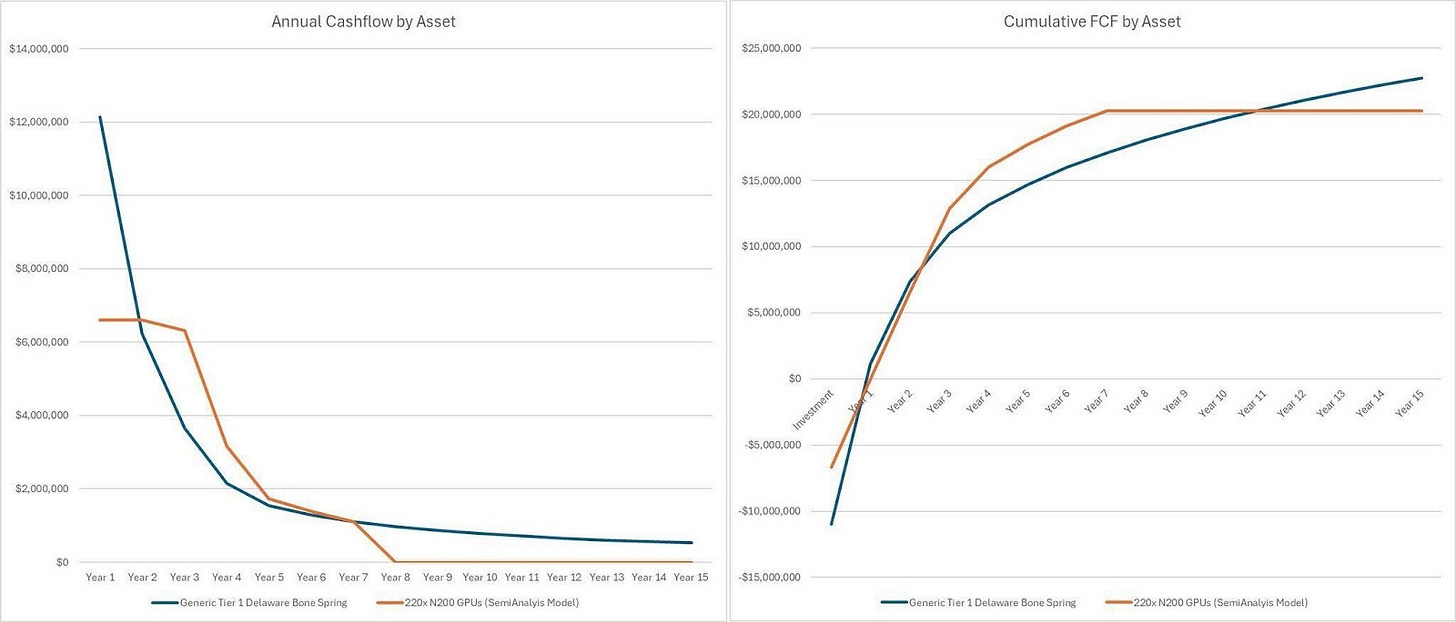

Special thanks to Michael Spyker for this side-by-side comparison

The Shale boom in the mid aughts began with a gusher of steady cashflows, but as time went on, each well generated less and less cash.

By year three of the shale rush, cumulative cash flows for “generic tier 1 bone spring” sites (a reference to the Bone Spring limestone in the Permian basin) began to stagnate. Shale projects went bust, and lots of investors lost money.

The similarity between the shale depreciation curves and GPU depreciation curves drives the doom porn home: if you spend lots of money upfront for an asset that prints money, you better hope that asset keeps printing money for long enough to generate returns on your investment. And just because it looks good early, doesn’t mean that market conditions will continue to support that investment later on. ‘Every shortage becomes a glut’ is the adage, and it certainly applied with respect to energy.

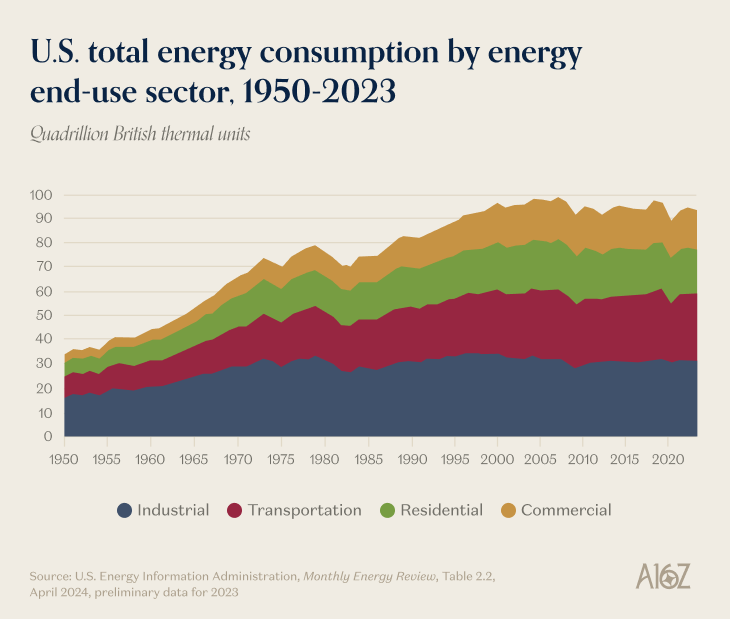

The difference with AI - or at least, what we all think is the difference - is whether Jevons kicks in, and the demand side materializes. It would be like the Daniel Day Lewis character in There Will Be Blood worrying “but what will happen, once we’ve satiated their demand for whale blubber?!” Well, it turns out that there were a lot more useful ways to consume energy than burning the midnight oil.

What ways? Mostly, we’ve got no real idea, much the same way a 19th century oil baron could never have imagined that an explosion of hydrocarbons would launch an entire world of plastic. Or, the first time we read Attention is All You Need, it’d be hard to imagine that in less than a decade we’d have reinvented computing around agents talking to each other:

And who knows, maybe all of those new use cases that pull Jevons forward are going to be worked out by the agents themselves: the LLMs are going to do the lions’ share of figuring out all the new and different ways to use LLMs.

That’s pretty crazy, indeed.

This newsletter is provided for informational purposes only, and should not be relied upon as legal, business, investment, or tax advice. Furthermore, this content is not investment advice, nor is it intended for use by any investors or prospective investors in any a16z funds. This newsletter may link to other websites or contain other information obtained from third-party sources - a16z has not independently verified nor makes any representations about the current or enduring accuracy of such information. If this content includes third-party advertisements, a16z has not reviewed such advertisements and does not endorse any advertising content or related companies contained therein. Any investments or portfolio companies mentioned, referred to, or described are not representative of all investments in vehicles managed by a16z; visit https://a16z.com/investment-list/ for a full list of investments. Other important information can be found at a16z.com/disclosures. You’re receiving this newsletter since you opted in earlier; if you would like to opt out of future newsletters you may unsubscribe immediately.

There are serious limits to the comparison to the shale boom. Notably, there were contractual reasons why companies had to drill when acquiring land rights. The land grab drove excess capacity which drove down price. There is limited demand elasticity for natural gas. The weather is the weather and utilities contract for price anyway. Again, limited value in the comparison.

Brilliant. My book collectin is Jevons in action.