Going to market when no market exists

How to price and sell a product when creating a new category

| America | Tech | Opinion | Culture | Charts |

As we head into the holidays, we’re revisiting some older pieces from the archives that still resonate today. Today, we’re bringing back an incredibly useful primer from Martin Casado on how to go-to-market when you’re creating a new category. Seven years later, this talk is still S-Tier idea-dense, practical, tactical advice. Here it is, lightly edited for clarity.

(Also, we’ll be off tomorrow for Thanksgiving, and back Friday with Charts of the Week.)

Up front: this primer is not about blocking and tackling. This is not a business course. This is: 1) as a technical founder in a market category creation scenario, what are my lessons learned? And, 2) if I would’ve gone back, what I would’ve done very differently.

What I mean by market category creation is, when we started Nicira, the concept didn’t even exist. There’s no idea. We built this thing and nobody knew how to think about it. Gartner didn’t know how to talk about it. There was no budget. There was no line item in anyone’s budget to spend on it.

And I think one of the biggest logical fallacies that technical founders do is the following: they think that if you create a widget, it has intrinsic value. And anybody that runs across that widget will be able to not only understand how cool it is, but also the dollar of value attached to it.

The reality is that no matter how cool your widget is, especially in the enterprise space until you go through go-to-market, it’s like it doesn’t even exist. Nobody’s gonna come and buy it. Most material on go-to-market that you’ll find in the general literature is around mature markets, where you do things like market research and how to do pricing and comparative analysis, but none of that applies in market category-creation scenarios.

So, let’s say you have this moment of inception: you’ve created this thing that’s only yours. How do you take that to market and get people to understand it and value it and sell it?

So it turns out, at least in the enterprise space, pretty much all of the value of a company comes down to go-to-market. And this was very non-intuitive to me at the outset, but go-to-market is at least as important as technology, and if you want a very simple mental model of why that is, it’s the following:

Over time, R&D becomes a fixed cost, or at least a sublinear cost. It’s R&D; it’s not going to scale with the number of customers. That’s not the case with sales. And in most market category creation situations, you have to have a warm body selling to the customer, because the customer doesn’t even know how to think about it. In most cases, you have a direct sales model. And that direct sales is going to dwarf your fixed cost by far: 1) it becomes all of your variable cost, therefore 2) that will become your margin, and therefore 3) that will set your valuation.

Here are the key decisions you’ll have to make that will impact the valuation of your company more than any other decisions; independent of how good the technology is.

First off, how do you know if you’re in a market category creation situation? If you’re developing new technology, sometimes you’re actually entering an existing market. Let’s say you make a hard drive that stores more information, or you make a router that’s faster, or something like that. In this case, this isn’t market category creation because the customer actually knows what you’re talking about. They know how to buy, and you’ve got very clear metrics. In which case, this probably doesn’t apply to you.

Market category creation is when the customers don’t even understand the technical concepts.They don’t understand the approach. In many cases, they don’t even know they have a problem. It’s very difficult to sell somebody something when they don’t even know a problem exists. Because not only do you have to educate them on how your technical solution isn’t snake oil, you also have to educate them that the way they’re doing things doesn’t work. And in some ways it’s very difficult to do that without calling the baby ugly. You’re like, “Listen, what you’re doing is not right, and I’ve got this thing that’s a little bit better and you’ve never heard of it before.”

If you feel like you’re going to market and you’re having hard customer conversations and they don’t really understand what you’re talking about, and you know that there’s something there but they don’t really see it, you may be in a market category creating scenario. If you’re saying, “Here’s widget X and mine’s better for these reasons”, you probably aren’t. And good for you; I think it’s much easier in that situation.

Okay, so what do we mean by go-to-market? The classics that you get in business school are: pricing, promotion, marketing placement, and positioning. I’m gonna focus on pricing, marketing, and sales.

I remember early on, when Ben Horowitz was on my board, we were thinking about pricing. And he told me something I remember very clearly - and I didn’t understand until much, much later how true this is - that there’s no single decision, at least in enterprise, there’s no single decision you’ll make that is more important than pricing with respect to your valuation. Not a single one. If early on you set your price too low, you’ll basically cannibalize your entire future market, and it’s very difficult to raise prices.

So then there’s this open question: how do you set a price when no market exists, and nobody knows how to value whatever you’re doing?

First, a caution. I’ve seen this across at least ten companies in the portfolio, and it’s a mistake technical entrepreneurs do, which is thinking the hard part is distribution as opposed to value. This was a big mistake I did.

What happens is, we optimize product entry in order to get it to as many people as possible, at the risk of price. We assume that, because we’re technologists, we can innovate, and on top of that, that we can upsell. So our intuition is, “if we set a price low, a lot of people will use it, and then I’ll have account control and traction, and then I can use that as a leverage point to make more money.”

In almost every case that I’m familiar with, that I’ve done, that’s actually not what happens. If you’re having a hard time selling something early on, it’s almost never because of price. It’s that the market’s not ready, or you actually don’t have product market fit, or you don’t have the right sales model. We often make this assumption that you have to price really low or you don’t enter the market at all. And many cases will show this as false.

So: you created Widget X, you’re trying to bring it to market, and you know you need to set the right price, because if you get that wrong, you’ve screwed your company. So the question is, what is the right price to set it up?

The way that you normally would think about this is to find comps, and find what the customer is able to pay, and so forth. And the reality is, you almost have to work at it backwards, and start with: What sort of sales model can you do? And then what sort of price will affect that sales model? Certain prices will support certain sales models, and other prices won’t.

So for example, in most enterprise market category creation scenarios, you have to do direct sales. Direct sales means that you’re paying a sales rep, let’s say $300k a year OTE (“On-target earnings”). How many deals can they normally close in a year? In my experience, max 10, average around 6. So the maximum they’ll be able to bring in, if you price at 100k, is $600k a year. This is a natural law of physics if you’re doing direct sales, which means your margin is now 50%, if you do 300k OTE.

And if you identify, “Listen, we have to do direct sales, because our product is only applicable to the Fortune 2000 and is a category creation situation. So we need a sales rep to have that deep conversation, get evangelists, and so forth.” Well, if your ACV isn’t actually quite a bit higher than that, it’s unlikely you’ll have a viable company, full stop. And if you set it too low initially, it’s very difficult to raise it.

We’re actually starting to see a lot of success, even in market category creation scenarios, where you actually are using inside sales. But what’s interesting is that revenue is still correlated more to direct sales: it’s as if inside sales is to bootstrap a sales function. Because even if you say, “We’re gonna start an inside sales model, so I’m fine with a low ACV.” (Which, for the majority of companies I talked to, that’s their intuition.) What happens is they run into this wall where they basically trained the market. The market has never thought about your thing before; now you’ve trained them that it’s worth 40K. It. And you’ve done that for two years now, the market value is your new thing at 40K, and now you’re trying to build a direct sales model. It’s very difficult because you’ve just cannibalized yourself upfront. So you need to think very deeply about what you can price versus what sales model that you need.

You can experiment a lot early on, but you can’t experiment too much. An entrepreneur basically has two challenges in market category creation situations. Challenge number one is you have to create a concept. Your constituency wakes up in the morning, they think about all sorts of stuff, but they don’t think about your thing ‘cause it doesn’t exist. So you create it. Now the first thing you gotta do is get ‘em to think about your thing. That’s step one. But step two is you have to attach a value to that thing.

Things in people’s brains don’t have intrinsic value. It’s in a conversation, in a transaction, where these things happen. I would strongly recommend that you do a lot of this work upfront to understand the natural law of organizational physics around pricing and around sales before you start cementing that dollar value on that thing in somebody’s head.

By the way, when I say “Think hard about your pricing model”, sometimes I see people really take that to heart and they come back with an unbelievably complex pricing model for a pipsqueak four-person startup. That’s not what I mean at all. Focus on the high order bit. The high order bit here is, “What ACV do you need to drive the sales that you need to mature your market. That’s the high order bit. A lot of times, I think start-ups try to look a lot more mature than they are, and so they’ve got 50 pricing models and 5 different consumption paradigms. In the very beginning, I’d keep it very simple. I’d tag the price very high.

It’s very seductive to think about bundling with a more mature product; never do that. You might say, “Here’s a big product, Windows. If I’m bundled in Windows, it solves my distribution problem. I’m done.” The problem is, if you draft on another buying motion, then the people are buying that other thing, they don’t care about your thing. Microsoft is notorious for making multiple billion dollar businesses of basically shelfware because the consumption behaviour didn’t change. Price however you can; make sure it’s an independent SKU and an independent sales motion.

In my experience, be very careful about SKUing. And by SKUing I mean “offering different price points with different feature sets.” If you’ve done it before and you’re comfortable with it and it’s a mature market, that’s fine. In my experience, you need to anchor high, because it’s very difficult to go high; and then once you start SKUing, your mental model should be market expansion, net cannibalization. That’s the only reason why you want to SKU. But markets are really good at finding lowest price points. You start becoming your worst enemy as soon as you start doing that. Your life will be much easier if you resist doing that for a while.

Let’s talk a little bit about discounting. This comes from the enterprise buyer perspective.

One thing that salespeople are phenomenal at is actually understanding the procurement process. It’s this very baroque, tribal thing that happens: this dance that you do, and different enterprises have different buying behaviors. But in almost all of them, you have your technical discussion, your technical sale, and then you get kicked over to procurement. And then these guys are actually comped on discounts. There’s an expectation for a discount on the back end, and many of the large vendors will do 90 point discounts, 70 or 60 point discounts. If it’s in the early days and you’re worried about price erosion, it’s good to anchor that on something of value: “You’re an early customer, so we’re doing this.” If you can get away with it - and it’s hard to do - it’s really good to avoid doing any sort of public pricing until you’ve actually set the price in the market.

Over three product launches and billions of dollars of revenue for early market situations, the only way I’ve actually been able to find prices is through the sales motion. No amount of market research or comp analysis, in my experience, will do it. You don’t know what people are willing to pay and they don’t know what they’re willing to pay until you’ve really shown the value. In the time that you’ve shown the value, you’ve already de-risked the account. You’ve de-risked technical risk. You’ve de-risked organizational risk. So this is a year-long engagement cycle before you actually know what they’re willing to pay for these things.

The more that you can actually protect whatever the market’s notional pricing is until you get to where they’re actually willing to pay, the better. It’s not always possible, but I don’t think we ever listed pricing.

Marketing

Marketing is incredibly technical, and it’s becoming exceptionally technical as developers become a buying center. It’s actually also one of the best moats you can build around your company.

When I think about marketing, I think of it in three terms. There’s Product Marketing, which does two functions: 1) “What’s your story” and 2) sales enablement. Demand Gen (“Field marketing”) is: “You’ve got the entire world; reduce it to a set of people that I can chase after.” And then branding, which I’m not gonna talk about because that’s an art that I actually don’t understand.

The thing about being an entrepreneur, especially an early entrepreneur, is in the very beginning, the only currency you have is magic beans. You have nothing else. You have a story for entrepreneurs, a story for investors, for early employees; you have nothing else. You’ve got four other people. You don’t have a product, and if you do, it doesn’t work.

And the problem with these magic beans is, you’re really used to them, because you live with them all the time. So you know why they’re awesome, but nobody else does. And you normally only have about 10 minutes to tell other people why they’re so awesome. So you’re putting everything into this currency, but it’s gotta be as simple as possible.

We probably spent six months just refining the story of value. Six months, and it was six months of every day. And it’s so hard to do. You’re sitting there, it’s this grueling triage, because you keep cutting down the story, it’s like cutting off parts of your body, but you end up with something that’s actually meaningful. It has to be simple. So invest a lot in it.

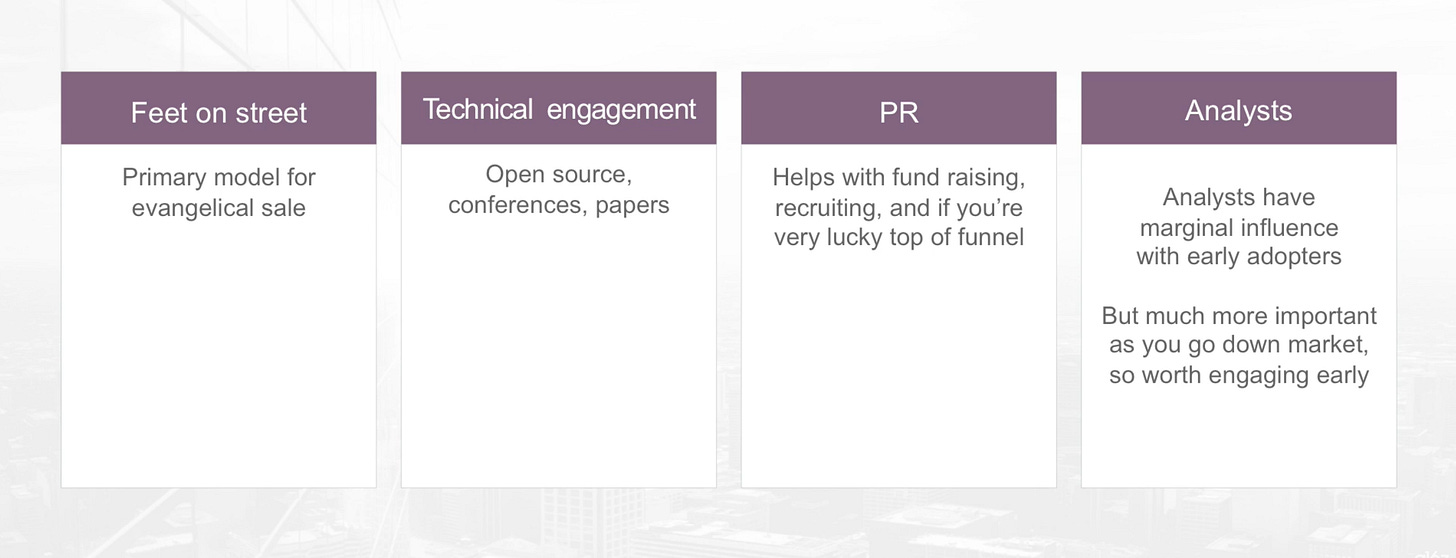

Let’s talk about marketing channels. In my experience, feet on the street - whether it’s you, your sales teams, or somebody talking to customers - is the primary channel for dissemination in early markets. You can write articles, but they rarely create concepts in people’s brains and they rarely create value. You can do press, it’s fine, but I’ve found press better for recruiting in the early days than market category creation.

Analysts actually are very important. It’s interesting: when you’re dealing with the early adopters, they don’t really listen to analysts because they’re often kind of Wild West and they’ll engage with you directly. But as soon as you go down market, Gartner’s really important. Believe it or not, you have to do your own market category creation with Gartner. I always thought it was really ironic: the first time you talk to Gartner about your idea, they don’t know what it exists. So it’s this kind of mini assault that you have to do in order to get them to agree, and then they’ll affect buying motions.

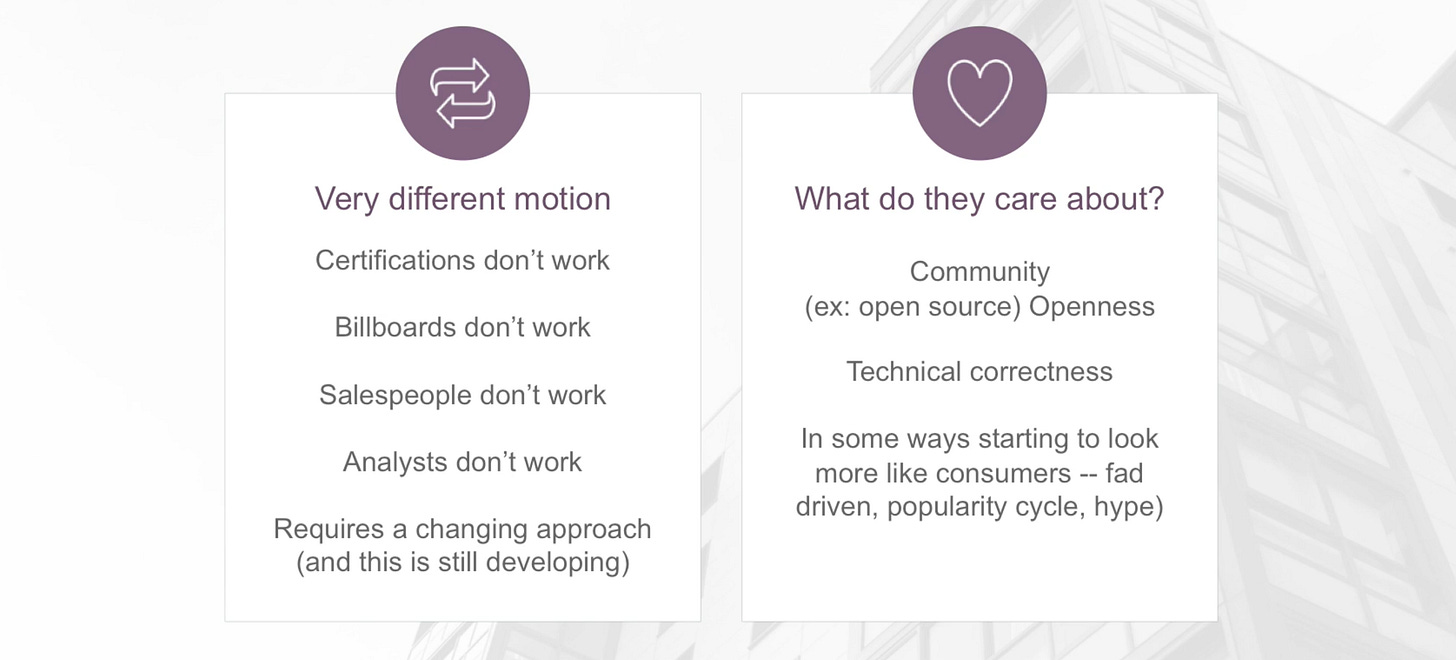

So I think one of the most significant changes that’s happening in all of the enterprise is that developers control budget now. Traditionally, the power and the moat of all the incumbents like IBM and Cisco and Oracle was, they owned the accounts. And what I mean by owned is, they trained all the people there. They own the channel partners. They have all the certifications. They’ve got account relationships that go back 40 years, and they’ve got 500 people there. That’s been one of the most difficult things for startups to overcome.

All of that’s changing right now, because developers are influencing budget more than ever. And they’re changing in a way that’s really beneficial to you. They’re way more technical. They don’t care about these relationships. They like to consume things on more of an Amazon-like basis. They actually don’t care as much about analysts. They definitely don’t have the same relationships with the box seats or the nice dinners. It’s a very different buyer.

The problem is nobody really knows how to get to them. We’re all trying to figure out what excites developers. And here’s what most people will tell you: “You can do freemium and you can do hackathons.” And I’m not sure if any of that works. We’ve gone through probably 200 companies that have tried these things, and you’ll see open source projects that do roughly the same thing. One takes off and one doesn’t take off. But I will say that, if you attract developers, you have something. That is something that has influence with an organization as long as you don’t run into the other pitfalls, which importantly, there are a few.

Just because you have a lot of developers that like your thing doesn’t mean you’re done. Developer budgets tend to be very fragmented and small / low consumption, not long-term. Often when you get to the larger budgets, you’ve gotta deal with procurement anyways. In general, when we have seen companies come in that have open source strategies that create large top of funnels for developers, you get nice super linear revenue ramps to a hundred million plus, once they build direct sales.

You should think very seriously if you can still build out direct sales to sell to other parts of the organization like core IT, because I would say the majority of the successful companies we see, that was the model they did: the open source thing people love; sell to Core IT on the operation side.

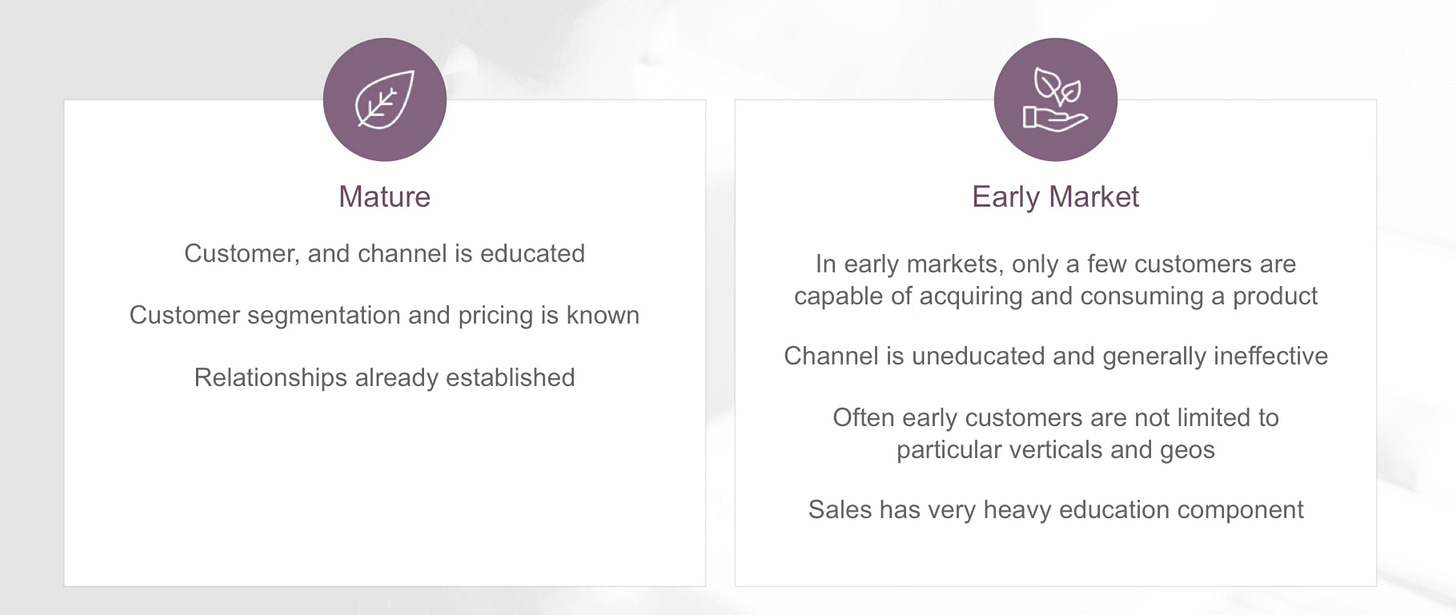

A common mistake, and one that I made many times, is to think that sales is sales. Early market sales is different from mature market sales. And the people that do well in early market sales are often very different from people that do well in mature market sales. And the reason is it’s just a different motion.

In mature markets, the customer’s already educated. They already know about the widget. They already know about the competitive landscape. They already know about the risk profile. They know what’s gonna happen. So it’s much more of a relationship / commercials- type discussion. It doesn’t really matter to talk about technology because you only talk about technology when it’s being created.

Whereas, in early market sales, it’s technology led. You’ve gotta qualify really hard, you’ve gotta be a “renaissance”; it’s a very different motion. There’s a framework I found very helpful called the Sales Learning Curve. I usually don’t like these general frameworks, but this one I really like, and it gives you a simple mental model.

As markets mature, a single sales head in the early days won’t even break even. One way to know you’re still in an early market is if you think you’ve got product market fit, you feel like the market’s maturing, but you’re hiring sales folks are not breaking even. The types of sales leaders that you want at this time, very self-initiated, understand how to use an SE, a sales engineer, often know how to pull in multiple parts of a sale, multiple parts of an organization. Qualify very aggressively. It’s a very specific time. Some people call them “hunters”; you can call ‘em whatever you want.

Whereas at some point you get more productivity, until we get to about two to three times OTE: you’ve hit a mature market. Then you’ve got very much coin operated numbers, sales folks that will really get out there and hustle and drive sales.

At some point in time, you actually have to shift your sales organization. Sometimes, with a really good sales leader, they’ll do that shift for you. They know how to manage the team, they’ll do the training and everything else. In our case, we had to do a reset. It’s not fun. So, definitely know that there’s a different skill set early versus later.

One of the most disruptive things in a startup, in my experience, is you build out your sales team ‘cause you’re really excited, you got one customer win, a lot of people are talking about you, you hit Hacker News; so you get a sales team. And then all of a sudden they’re not hitting quota and they’re frustrated. Now, all of a sudden, you’ve got something that’s starting for oxygen that’s gonna reach into your organization. And now they’re pushing on the engineering or the PM to build this one feature to get the deal. They’re pulling in the wrong types of deals, they’re not qualified customers.

So do whatever you can to survive and only turn things on once you really feel like you’ve got product market fit. Because something honestly that’s worse than having no sales team and no numbers is a sales team that’s starving for oxygen. They can be so disruptive; not only to morale, but to the internals of the organization. And you really start missing market signaling; just because they’re looking for anything that they can do to get something in.

Sales reps, account manager, account exec, account rep, whatever you want to call it: in early markets, often the sale is done by a sales engineer, who’s actually doing the sale and getting it to technical close.

So normally what happens is, the account rep will find and qualify a deal, whereas the sales engineer will actually bring it to technical close. The actual selling is on the technical side. Mature market sales engineers look more like a support type resource, where early market sales engineers are about evangelical sales; almost like a mini CTO.

Here’s a typical sales engagement model. Introductions, you do a proof of concept, maybe a pilot, then you get to technical close. If at all possible, don’t talk about pricing until here, in the early market. And the reason is, there’s no way they can actually value your solution, because they’d never thought about it before, until you get to technical close. And so it’s a very difficult thing to do. Customers are very trained to talk about pricing early on.

Your limiting resource is often your startup capacity. Oftentimes, entrepreneurs are a little deluded and super smart about an area, and they know everything about it, and spend their entire lives becoming libraries of knowledge about the space. And that is valuable to any buyer, and they will happily listen to you, and even pay you $50k here, 100k there, just to learn from you. You can get glue-trapped in an account for years without getting to a real deal. All the while, you’re burning your internal capacity to address their need.

Another thing that large buyers will often do is actually turn you into a contract engineering shop. It often looks like, “Wow, if I just put in this one more feature, I’m going to have this big huge account!” But unless you’re working towards a repeatable product in market, you’re contract engineering.

Professional services

The following is a very “Non-VC” thing to say, but I want to point it out.

What are professional services? If you’re selling to a customer and they ask, “Will you take $300k to actually help us implement the product and do professional services?” Now the standard VC logic is, you don’t do that because they’re low margin, shitty businesses. In early markets, though, sometimes it’s required. And it’s required for two reasons.

The first one is the customer wants to pay you that money, because they want that assurance. It’s not unusual for a pre-chasm enterprise product to have 50% license and 50% professional services. Now, VCs will hate it, investors will hate it, because it’s this big low-margin business. But actually to get the deal done and to actually implement it correctly and to offload that cost, it’s required.

What’s even more important, and less talked about, is ultimately that professional service has to happen sometime, especially for complex products. Somebody’s got to do it. Either the customer does it or the partner ecosystem does it. The ideal case is the partner ecosystem does it. But most partner ecosystems you can’t incent without actually having a market. They’re not going to train all their folks to do professional services for a market that doesn’t exist. So many companies will actually do PS, they’ll actually take money for professional services, they take it on license, they build a market and then they will offload that to the partner ecosystem once you have a real market.

Another one of the most seductive thoughts to a startup is indirect sales. And I think it’s one of the biggest mistakes; I put it in the top five. The mistake is the following:

“I’ve got a new product, I don’t understand go-to-market. HP will sell it for me, or IBM will sell it for me.” Here’s my experience: the channel - a reseller, an OEM, a VAR reseller - will only work in a pull-based market. If you’re in a pre-market situation, they just can’t do it. It requires too much evangelism. They don’t know it, it requires too much training. The channel won’t really work until it matures. It’s worth investing into for when it does, but it won’t drive your number. Most entrepreneurs I work with want to engage the channel early, because it feels like a shortcut, but it just doesn’t happen.

To summarize:

All companies come down to go-to-market, and you especially need to hear this if you have a technical background or a product background. R&D really does pencil out as a fixed cost; your go-to-market is what drives the business. So, understand it.

Story is crucial; over-invest in that. I do think that if you’re selling into a pre-market situation, if you can do direct sales, you should. ISR is great for top-of-funnel and inside sales is great to get things going, but you need to have a plan to get to direct sales. Figure out this stuff as much as you can beforehand, especially with pricing, so you don’t cannibalize yourself before you get started. It’d be great for a channel to save you, but it probably won’t.

With that, thank you!

This newsletter is provided for informational purposes only, and should not be relied upon as legal, business, investment, or tax advice. Furthermore, this content is not investment advice, nor is it intended for use by any investors or prospective investors in any a16z funds. This newsletter may link to other websites or contain other information obtained from third-party sources - a16z has not independently verified nor makes any representations about the current or enduring accuracy of such information. If this content includes third-party advertisements, a16z has not reviewed such advertisements and does not endorse any advertising content or related companies contained therein. Any investments or portfolio companies mentioned, referred to, or described are not representative of all investments in vehicles managed by a16z; visit https://a16z.com/investment-list/ for a full list of investments. Other important information can be found at a16z.com/disclosures. You’re receiving this newsletter since you opted in earlier; if you would like to opt out of future newsletters you may unsubscribe immediately.