Bitter Economics

Software companies and their new relation to capital

| America | Tech | Opinion | Culture | Charts |

The direct consequence of the bitter lesson is that we’re building systems that turn large amounts of capital into working solutions. I would argue that this goes a long way toward explaining why company growth rates and funding are so different this AI cycle. And in the long run, this will be the most important and transformative aspect of AI.

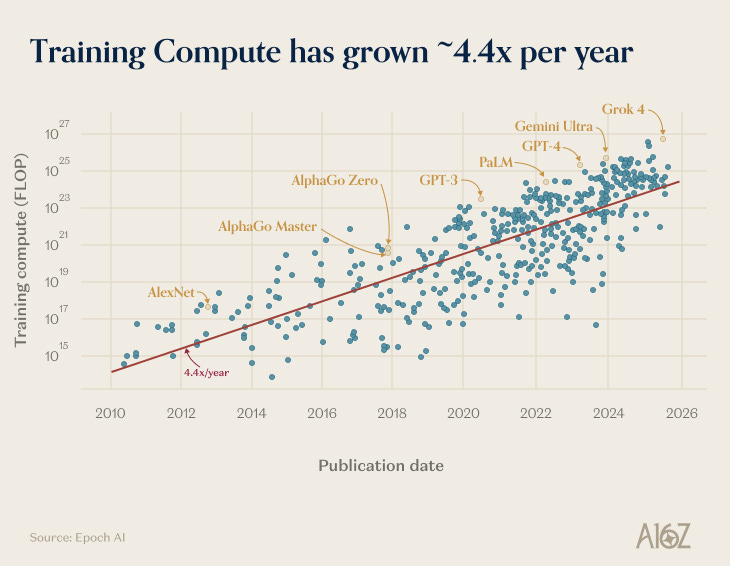

Let me explain. The bitter lesson is an oft-cited essay from Richard Sutton which posits that the AI methods that end up winning are those which most directly use compute. When faced with a trade off between clever algorithms, clever engineering, and brute force compute, it’s best to choose the latter. This allows the approach to benefit from the dramatic increase in availability of compute, not just due to Moore’s law, but because AI training and inference can be parallelized, it can benefit from the increasing amount of GPUs we can cram into a large datacenter.

True to Dr. Sutton’s observation, this is roughly how AI systems are built today. Relatively small teams, with lots of resources for data and GPUs, can build tremendously powerful systems. Systems that become more powerful the more data and money you pour into them. In fact, we’ve gotten so good at scaling AI with GPUs that power not compute is the primary limitation.

This simple, almost tautological, result of Sutton’s observation entirely changes software companies, and their relation to capital.

Prior to this AI cycle, nearly all compute endeavors ballooned into complex engineering problems. And there is a very hard limit to how fast one can scale software by throwing money and head count at it. In fact, it’s been widely known for decades that more investment in software projects are often counter productive, a primary thesis behind Fred Brook’s The Mythical Man Month.

The inability to deploy large amounts of capital productively in traditional software projects has limited the pace of innovation, and has kept the scope of ambition in check. The truth is, we’ve not been capital constrained, but constrained by the ability to amass and coordinate talent and limited by the inherent difficulty in fighting against growing complexity in large engineering projects. Significant software projects often take years to develop and teams of thousands of people. As early stage investors we routinely see that over-funding is most often deleterious to a startup.

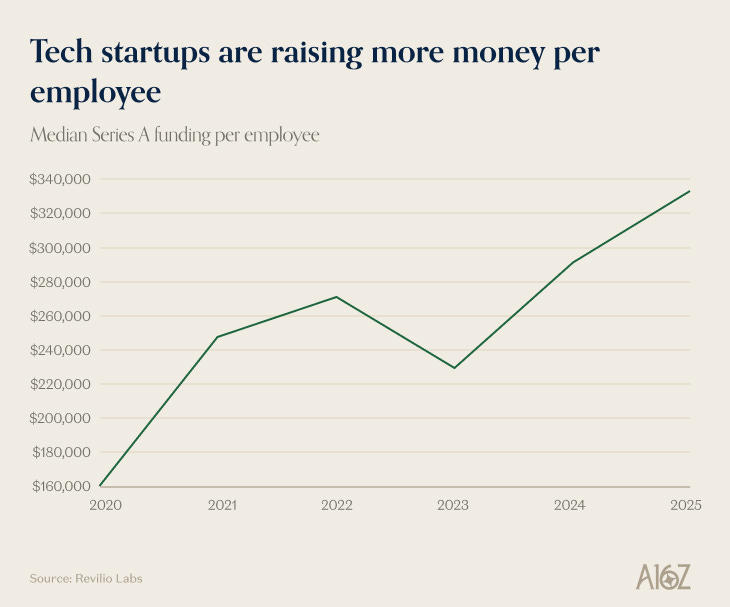

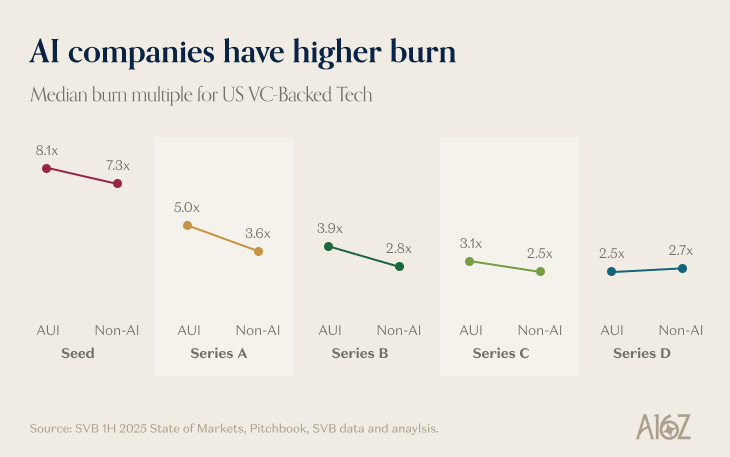

AI projects, on the other hand, are taking far more capital, by far smaller teams, and turning that into historic growth rates for both new users and revenue. Moreover, the result in many cases are tremendously powerful products that tackle a broad range of solutions. This massive success has engendered an entirely new level of ambition and optimism we’d largely lost as an industry.

What does this mean in the long run? First, there is an entirely new class of problems we as an industry are going to tackle. The two primary considerations are (a) do we have enough data and GPUs to tackle them? (b) is the solution sufficiently useful that we can recoup the costs? Further, funding dynamics are already changing and I suspect that will continue. Some sectors will see a lot more money invested earlier. And as a consequence we should see a commensurate spike in early company growth and of course burn. There are clear indications of this now. But I suspect we’re still in the very early innings.

Does this spell the end of traditional software? Far from it. AI is often a tremendously inefficient way to solve a problem. As Andrej Karpathy points out, it’s most suitable for situations that are hard to specify but possible to verify. Creativity, language reasoning, math, code and many areas in science fit this definition and indeed we see a lot of progress in them already. It’s far more economically sensible for AI companies to go after massive markets traditional software is less suitable for and thus we have yet to tackle effectively. So while many traditional software markets have slowed down due to shifts in budget to AI, it’s unlikely AI will obviate or replace many of them in the foreseeable future.

Does this mean we will see a diminishing need for software engineers? Unlikely, although it’s fair to expect the role to evolve as tooling for AI development matures (including the use of AI to generate large tracts of it). This allows engineering teams to be far more productive for certain classes of problems, particularly with ample GPUs, and broadens the range of problems they can tackle. There’s a reason the fastest-growing AI companies are hiring software engineers as fast as they can.

Much discourse on AI’s long term impact on the economy centers around speculation on when we will achieve AGI, and what that will mean. I’d argue that whether or not AGI emerges from a single model, the impact of this meta economic machinery is functionally similar. That is, it reduces a massively broad class of technical problems to simply a matter of economics.

Sutton’s lesson is bitter to AI researchers because smart people like smart solutions. Yet on the winning path, compute overrides cleverness. To investors, I’d argue it is also sweet. Because it allows steady and scalable deployment of capital to talented teams and companies without destroying them. At least until we hit the next wall of complexity.

This newsletter is provided for informational purposes only, and should not be relied upon as legal, business, investment, or tax advice. Furthermore, this content is not investment advice, nor is it intended for use by any investors or prospective investors in any a16z funds. This newsletter may link to other websites or contain other information obtained from third-party sources - a16z has not independently verified nor makes any representations about the current or enduring accuracy of such information. If this content includes third-party advertisements, a16z has not reviewed such advertisements and does not endorse any advertising content or related companies contained therein. Any investments or portfolio companies mentioned, referred to, or described are not representative of all investments in vehicles managed by a16z; visit https://a16z.com/investment-list/ for a full list of investments. Other important information can be found at a16z.com/disclosures. You’re receiving this newsletter since you opted in earlier; if you would like to opt out of future newsletters you may unsubscribe immediately.